By Savanna Hoover |

It’s gameday in College Station, late September. Maroon and white tents cover the campus. There’s an electric spirit in the air, an energy beginning to build momentum. Standing next to the A.I. Engineering building’s yellow brick walls, underneath a line of concrete carved cattle heads, 10 nuclear engineering students split into two groups of five — half walking and half riding in a golf cart. The students place a radiation detector, housed in a PVC pipe, on the back of a golf cart. Another student carries a handheld detector. They begin to roam campus, from Spence Park to the Memorial Student Center to West Campus.

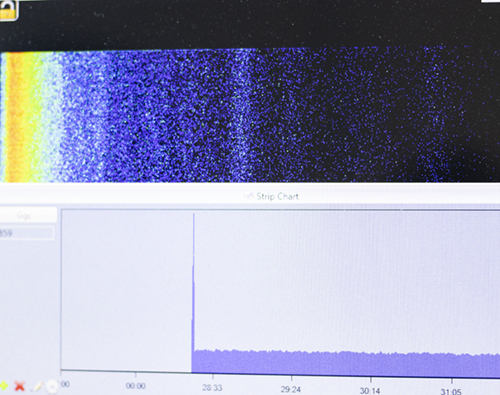

The heat and humidity are an invisible steam rising from the pavement. People are enveloped by the shade of the tents and old oak trees. One student drives while the rest watch the radiation detection mapped out on a laptop. The results from radiation detectors spike in certain areas like the red brick of buildings and the Texas A&M University seal on Military Walk. “These background radiation increases are normal and perfectly safe,” said Dr. Craig Marianno, assistant professor of nuclear engineering and the Deputy Director of the Center for Nuclear Security Science and Policy Initiatives (NSSPI). “Certain materials and structures have naturally higher radiation than others.”

“I started the tailgate sweeps because nuclear sweeps happen on a daily basis in the U.S. and I wanted to share those challenges,” said Marianno. “I also wanted to provide my students with an experiential learning opportunity.” Nuclear security professionals use radiation detectors to scan, or sweep, an area. Typically, they scan more at-risk areas such as political rallies. The tailgate sweeps provide an exciting and safe training opportunity for nuclear engineering students to explore hands-on field work with detectors and see how nuclear security can be applied at large events. Several of his students have graduated and gone into the nuclear security field, and Jonathan Chen ’18, the undergraduate student of the year, hopes to be one of them.

Chen knew in his first year of nuclear engineering that he gravitated more toward homeland nuclear security than the nuclear power field. He took a bold step forward by emailing a professor he had never met and introducing himself. That professor was Marianno.

Even though Chen was only a sophomore, Marianno let him join his radiation detection research group and participate in the sweeps, which are geared toward his graduate class, “Nuclear Engineering 605 Radiation Detection and Nuclear Material Measurements.” For the next three years, Chen helped out with the game day event, which on most years meant four game sweeps per football season.

Chen advanced in his studies and began leading tours himself. His favorite part? Seeing the students’ faces as they complete radiation detection readings outside the lab for the first time.

Chen thinks it’s important for students to know that there are many career options in nuclear engineering beyond working in a nuclear power plant. The game day sweeps have inspired him to pursue a nuclear national security career himself. “The sweeps, the Center for Nuclear Security Science and Policy Initiatives and the Institute of Nuclear Materials Management give you an increased understanding of the field and if this is something you would like to do,” he said.

The goal of the tailgate sweeps is for the student to observe how environmental radiation levels can change based on landscaping, building structures and other phenomena. If they found a higher than average radiation reading, then Marianno or his teaching assistants would unobtrusively localize the source in conjunction with the students. The readings would be analyzed by Marianno so he could determine the gamma-emitting isotope. In large events such as Aggie football games it is not uncommon to find radiation fields created by individuals who have been injected with medical radiation for diagnostic or therapeutic reasons. These short-lived radionuclides are typically used by doctors to visualize internal structures, such as a heart during a stress test.

Some examples of medical isotopes include technetium-99m and iodine 131 for diagnostic imaging, or fluorine-18 for positron-emission tomography (PET) scan, which uses radioactive labeled compounds to highlight different organs in the body. A person injected with radioactive tracers can be detected from a few yards away for several days following some medical tests. One thing they won’t pick up? Chemotherapy. The “chemo” in chemotherapy stands for chemicals and the treatment does not include radiation.

Marianno was originally a health physicist before switching fields to national security with a focus on radiological threats. He spent 10 years with the U.S. government in nuclear incident response and consequence management. Now he teaches a mix of undergraduate and graduate classes on radiation detection, nuclear nonproliferation and emergency response dose assessments, while also training law enforcement and providing his expertise to the world.